Author: Huobi Growth Academy |

ExcerptWant

As institutional capital continues to increase its share in the cryptocurrency market, privacy is evolving from a marginalized demand for anonymity into a critical infrastructure capability for blockchain's integration into the real financial system. The public transparency of blockchain was once considered its most core value proposition. However, as institutional participation becomes the dominant force, this characteristic is now revealing structural limitations. For enterprises and financial institutions, the full exposure of transaction relationships, position structures, and strategy timing itself constitutes a significant business risk. As a result, privacy is no longer merely an ideological choice but a necessary condition for blockchain to achieve large-scale and institutionalized applications. The competition in the privacy sector is also shifting from "anonymity strength" to "institutional adaptability."

One,Institutional Ceiling of Complete Anonymity and Privacy: The Advantages and Challenges of the Monero ModelSituation

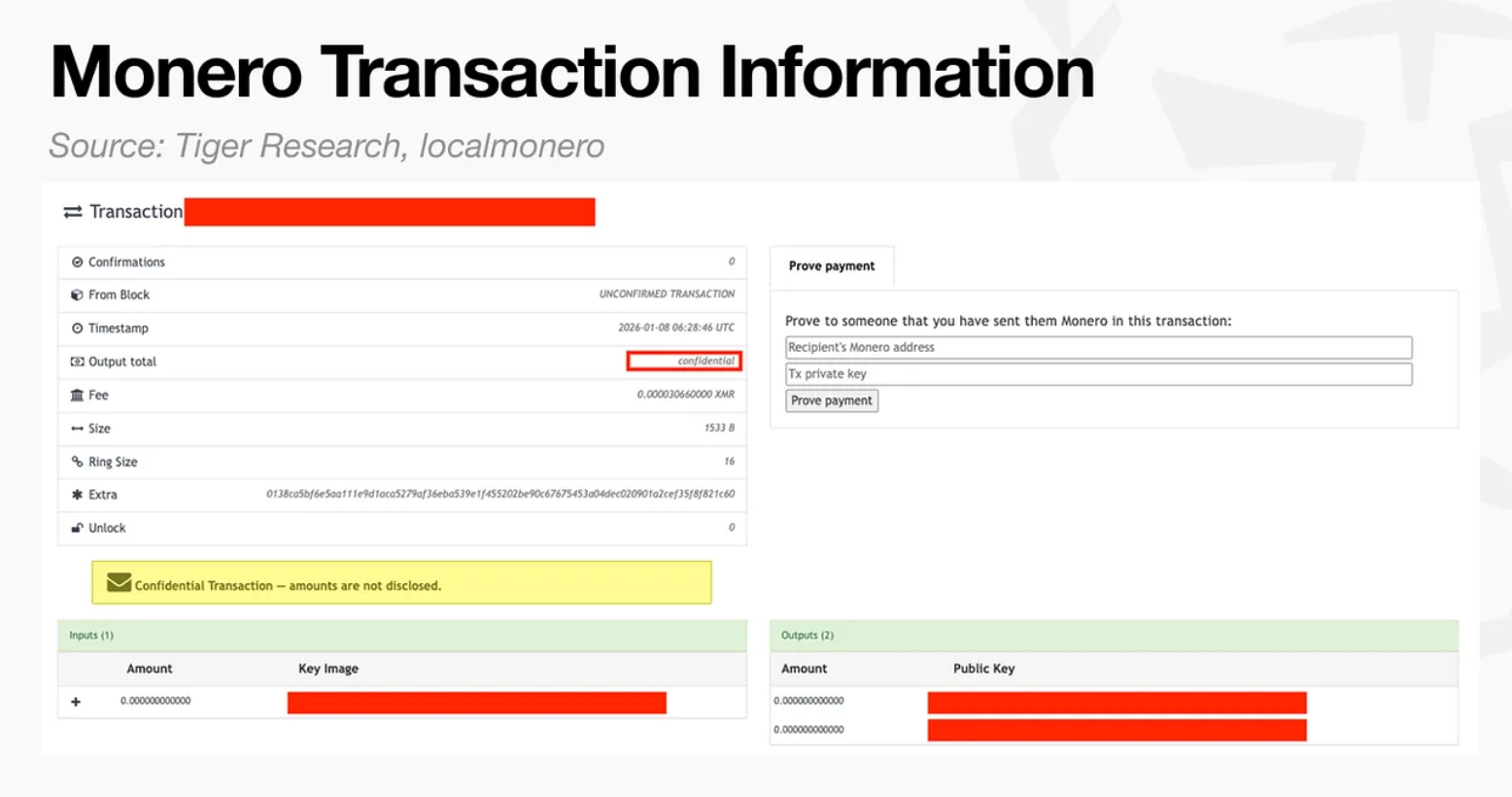

The fully anonymous privacy model represented by Monero constitutes the earliest and most "pure" technical approach in the privacy sector. Its core objective is not to strike a balance between transparency and privacy, but rather to minimize the amount of observable information on the blockchain and to sever as much as possible the ability of third parties to extract transaction semantics from the public ledger. To achieve this goal, Monero employs mechanisms such as ring signatures, stealth addresses, and confidential transactions (RingCT) to obscure all three key elements of a transaction: the sender, the receiver, and the amount. An external observer can confirm that "a transaction has occurred," but it is difficult for them to deterministically reconstruct the transaction path, the counterparties, or the value involved. For individual users, this "default privacy, unconditional privacy" experience is highly attractive—it transforms privacy from an optional feature into a system norm, significantly reducing the risk of long-term tracking of financial behavior by data analysis tools, and granting users anonymity and unlinkability in payments, transfers, and asset holdings that are nearly equivalent to those of cash.

From a technical perspective, the value of complete anonymity and privacy is not merely about "hiding," but more importantly, about the systematic design that resists on-chain analysis. The largest externality of transparent blockchains is "composable surveillance": the publicly available information of a single transaction is continuously pieced together, gradually linking to real-world identities through address clustering, behavioral pattern recognition, and cross-validation with off-chain data, ultimately forming a "financial profile" that can be priced and potentially abused. Monero's significance lies in raising the cost of this process to a level that alters behavior—when large-scale, low-cost attribution analysis is no longer reliable, the effectiveness of surveillance and the feasibility of fraud both decline simultaneously. In other words, Monero is not merely for "people doing bad things," but also addresses a more fundamental reality: in a digital environment, privacy itself is a part of security. However, the fundamental problem with complete anonymity and privacy is that its anonymity is irreversible and unconditional. For financial institutions, transaction data is not only essential for internal risk control and auditing, but also a legal obligation under regulatory requirements. Institutions must maintain a traceable, explainable, and submittable chain of evidence under frameworks such as KYC/AML, sanctions compliance, counterparty risk management, anti-fraud measures, and tax and accounting audits. A fully anonymous system permanently locks this information at the protocol level, making it structurally impossible for institutions to comply, even if they are willing to do so subjectively. When regulators request explanations of the source of funds, verification of counterparty identities, or details of transaction amounts and purposes, institutions are unable to reconstruct key information from the blockchain and cannot provide verifiable disclosures to third parties. This is not a case of "regulators not understanding technology," but rather a direct conflict between institutional goals and technical design—modern financial systems require "auditable when necessary," while complete anonymity requires "inherently un-auditable under any circumstances."

The external manifestation of this conflict is the systematic exclusion of strongly anonymous assets by mainstream financial infrastructure: delisting from exchanges, lack of support from payment and custody institutions, and the inability of compliant capital to enter the market. It is worth noting, however, that this does not mean the underlying demand disappears. On the contrary, the demand often shifts to more covert and higher-friction channels, giving rise to a flourishing of "compliance vacuums" and "gray intermediaries." In the case of Monero, instant exchange services have at times absorbed a significant amount of purchase and exchange demand. Users pay higher spreads and fees for accessibility, while also bearing the costs of fund freezes, counterparty risk, and information opacity. More importantly, the business model of such intermediaries may introduce persistent structural selling pressure: when service providers quickly convert the Monero fees they collect into stablecoins and cash out, the market experiences continuous passive selling unrelated to genuine buy orders, thereby suppressing price discovery in the long run. Thus, a paradox emerges: the more a digital asset is excluded by compliant channels, the more likely demand is to concentrate in high-friction intermediaries; the stronger these intermediaries become, the more distorted the price becomes; and the more distorted the price is, the harder it becomes for mainstream capital to assess and enter the market through "normal market" mechanisms, creating a vicious cycle. This process is not a matter of "the market not accepting privacy," but rather a result shaped by institutional and channel structures.

Therefore, evaluating the Monero model cannot be limited to moral debates; it should return to the practical constraints of institutional compatibility. In the individual world, complete anonymous privacy is a "default security," but in the institutional world, it becomes a "default unavailability." The more extreme its advantages, the more rigid its challenges become. In the future, even if the narrative around privacy intensifies, the main battlefield for fully anonymous assets will still primarily lie in non-institutionalized demands and specific communities. Meanwhile, in the institutional era, mainstream finance is more likely to adopt "controlled anonymity" and "selective disclosure"—protecting both business secrets and user privacy while being able to provide audit and regulatory evidence under authorized conditions. In other words, Monero is not a technological failure, but rather one locked into a use case that institutional systems struggle to accommodate: it has demonstrated the engineering feasibility of strong anonymity, yet it has also clearly shown that when finance enters the compliance era, the focus of privacy competition will shift from "whether everything can be hidden" to "whether everything can be proven when needed."

Second,The Rise of Selective Privacy

Against the backdrop of institutional limits increasingly constraining complete anonymity and privacy, the privacy sector is undergoing a directional shift. "Selective privacy" is emerging as a new technological and institutional compromise. Its core is not to oppose transparency, but to introduce a privacy layer that is controllable, authorized, and selectively disclosable, built upon a default verifiable ledger. The fundamental logic behind this transformation lies in redefining privacy: it is no longer seen as a tool for evading regulation, but rather as an infrastructure capability that can be absorbed and integrated into institutional frameworks. Zcash is the most representative early example of the selective privacy approach. Through its design that allows transparent addresses (t-addresses) and shielded addresses (z-addresses) to coexist, Zcash gives users the freedom to choose between public visibility and privacy. When users employ shielded addresses, the sender, receiver, and amount of a transaction are encrypted and stored on the blockchain. However, when compliance or audit requirements arise, users can disclose full transaction details to specific third parties by using a "viewing key." This architecture is milestone in concept: it was the first mainstream privacy project to explicitly propose that privacy does not necessarily require sacrificing verifiability, and that compliance does not inherently mean complete transparency.

From the perspective of institutional evolution, the value of Zcash lies not in its adoption rate, but in its significance as a "proof of concept." It demonstrates that privacy can be an optional feature rather than a system's default state, and it also proves that cryptographic tools can reserve technical interfaces for regulatory disclosure. This is particularly important in the current regulatory context: major jurisdictions around the world have not rejected privacy itself, but rather the concept of "unauditable anonymity." Zcash's design directly addresses this core concern. However, as selective privacy transitions from being a "personal transaction tool" to an "institutional transaction infrastructure," Zcash's structural limitations begin to emerge. Its privacy model is essentially a binary choice at the transaction level: a transaction is either fully public or entirely hidden. In real-world financial scenarios, such a binary structure is too coarse. Institutional transactions involve more than just the "two parties" dimension; they include multiple participants and multiple responsible entities—counterparties need to confirm performance conditions, clearing and settlement institutions need to know the amount and timing, auditors need to verify complete records, and regulators may only be concerned with the source of funds and compliance attributes. The information needs of these entities are neither symmetrical nor entirely overlapping.

In this context, Zcash is unable to modularize transaction information or provide differential authorization. Institutions cannot disclose only "necessary information"—they must instead choose between "full disclosure" and "full concealment." This means that once complex financial processes are involved, Zcash either exposes excessive commercially sensitive information or fails to meet even the most basic compliance requirements. As a result, its privacy capabilities struggle to integrate into real institutional workflows, limiting its use to marginal or experimental applications. In sharp contrast, Canton Network represents an alternative paradigm of selective privacy. Rather than starting from the concept of "anonymous assets," Canton directly begins with the business processes and institutional constraints of financial institutions. Its core idea is not "hiding transactions," but "managing information access rights." Through the smart contract language Daml, Canton decomposes a transaction into multiple logical components, allowing different parties to see only data fragments relevant to their permissions, while the rest of the information is isolated at the protocol level. This design brings about fundamental change. Privacy is no longer an afterthought or added attribute after a transaction is completed, but is embedded into the contract structure and permission system, becoming an integral part of the compliance process.

From a broader perspective, the differences between Zcash and Canton reveal the direction of differentiation in the privacy sector. The former remains rooted in the native cryptocurrency world, striving to find a balance between individual privacy and compliance. The latter, however, actively embraces the existing financial system, engineering, streamlining, and institutionalizing privacy. As the proportion of institutional capital in the crypto market continues to rise, the main battlefield of the privacy sector will also shift. The future competition will no longer focus on who can hide the most thoroughly, but rather on who can be regulated, audited, and widely adopted on a large scale without disclosing unnecessary information. Under this standard, selective privacy is no longer just a technical approach, but an essential path toward mainstream finance.

Three,Privacy 2.0: Infrastructure Upgrade from Transaction Hiding to Privacy ComputingLevel

After privacy was redefined as a necessary condition for institutions to join the blockchain, the technical boundaries and value scope of the privacy sector have also expanded. Privacy is no longer simply understood as "whether transactions can be seen," but is evolving toward more fundamental questions: can a system perform computation, collaboration, and decision-making without exposing the data itself? This shift marks the transition of the privacy sector from its 1.0 phase, characterized by "privacy assets / private transactions," to a 2.0 phase centered on privacy-preserving computation. In this new phase, privacy is no longer an optional feature but is becoming a general-purpose infrastructure. In the privacy 1.0 era, the technical focus was primarily on "what to hide" and "how to hide it," such as obscuring transaction paths, amounts, and identity associations. However, in the privacy 2.0 era, the focus shifts to "what can be done while maintaining privacy." This distinction is crucial. Institutions do not merely require private transactions; they need to perform complex operations such as trade matching, risk calculation, settlement, strategy execution, and data analysis under privacy-preserving conditions. If privacy only covers the payment layer and not the business logic layer, its value to institutions remains limited.

Aztec Network represents one of the earliest manifestations of this shift within the blockchain ecosystem. Rather than treating privacy as a tool to counter transparency, Aztec embeds it as a programmable attribute of smart contracts within the execution environment. Through a zero-knowledge proof-based Rollup architecture, Aztec allows developers to precisely define, at the contract layer, which states should be private and which should be public, thereby enabling a hybrid logic of "partial privacy, partial transparency." This capability extends privacy beyond simple value transfers to more complex financial structures such as lending, trading, vault management, and DAO governance. However, Privacy 2.0 does not stop at the blockchain-native world. With the emergence of AI, data-intensive finance, and cross-institutional collaboration needs, relying solely on on-chain zero-knowledge proofs is no longer sufficient to cover all scenarios. As a result, the privacy sector is evolving toward a broader concept of "privacy computing networks." Projects like Nillion and Arcium have emerged in this context. A common characteristic of these projects is that they do not aim to replace blockchains, but instead serve as a privacy collaboration layer between blockchains and real-world applications. By combining multi-party secure computation (MPC), fully homomorphic encryption (FHE), and zero-knowledge proofs (ZKP), data can be stored, accessed, and computed in an entirely encrypted state. Participating parties can jointly perform model inference, risk assessment, or strategy execution without ever accessing the raw data. This capability elevates privacy from a "transaction-layer attribute" to a "computation-layer capability," expanding its potential market to areas such as AI inference, institutional dark pool trading, RWA data disclosure, and inter-enterprise data collaboration.

Compared to traditional privacy coins, the value logic of privacy computing projects has undergone a significant transformation. They no longer rely on the concept of a "privacy premium" as their core narrative, but instead on functional irreplaceability. When certain computations are fundamentally impossible in a public environment, or when performing them in plaintext would lead to severe commercial risks and security issues, privacy computing ceases to be a question of "whether it is needed" and instead becomes a question of "impossible to operate without it." This also gives the privacy sector the potential for the first time to function as a kind of "underlying moat": once data, models, and processes are established within a specific privacy computing network, the migration cost will be significantly higher than that of a typical DeFi protocol. Another notable feature of the Privacy 2.0 era is the engineering, modularization, and invisibility of privacy. Privacy is no longer explicitly embodied as "privacy coins" or "privacy protocols," but is instead broken down into reusable modules and embedded into wallets, account abstractions, Layer 2 solutions, cross-chain bridges, and enterprise systems. End users may not even be aware that they are "using privacy," yet their asset balances, trading strategies, identity associations, and behavioral patterns are protected by default. This "invisible privacy" is, in fact, more aligned with the realistic path toward mass adoption.

At the same time, regulatory attention has also shifted. In the Privacy 1.0 phase, the core regulatory issue was "whether anonymity exists"; in the Privacy 2.0 phase, the question has evolved into "whether compliance can be verified without exposing the original data." Zero-knowledge proofs, verifiable computing, and rule-level compliance have thus become key interfaces for privacy computing projects to interact with the regulatory environment. Privacy is no longer viewed as a source of risk, but is redefined as a technical means to achieve compliance. Overall, Privacy 2.0 is not a simple upgrade to privacy coins, but a systematic response to "how blockchain can integrate into the real economy." It signifies that the competitive dimensions in the privacy sector are shifting—from the asset layer to the execution layer, from the payment layer to the computation layer, and from ideology to engineering capabilities. In the institutional era, privacy projects with true long-term value may not necessarily be the most "mysterious," but they will certainly be the most "usable." Privacy computing is precisely the concentrated embodiment of this logic at the technical level.

Four,EndOn

Overall, the core dividing line in the privacy sector has shifted from "whether to have privacy" to "how to use privacy in a compliant manner." Fully anonymous models offer irreplaceable security value at the individual level, but their un-auditable nature makes them unsuitable for institutional-level financial activities. Selective privacy, through its design of disclosure and authorization, provides a feasible technical interface between privacy and regulation. The rise of Privacy 2.0 further elevates privacy from an asset attribute to an infrastructure capability for computation and collaboration. In the future, privacy will no longer exist as an explicit feature, but will instead be embedded as a default assumption within various financial and data processes. Truly valuable privacy projects in the long run may not necessarily be the most "secretive," but will definitely be the most "usable, verifiable, and compliant." This is precisely the key indicator of the privacy sector's transition from the experimental phase to a mature stage.