Original Author: Nishil Jain

Original translation: Block unicorn

Preface

In the 1960s, the credit card industry was in chaos. Banks across the United States were trying to build their own payment networks, but each network operated independently. If you had a credit card from Bank of America, you could only use it at merchants that had agreements with Bank of America. When banks attempted to expand their services to other banks, all credit card payments encountered the problem of interbank settlement.

If the cards accepted by a merchant are issued by another bank, the transaction must be settled through the original check settlement system. The more banks that participate, the more settlement issues there will be.

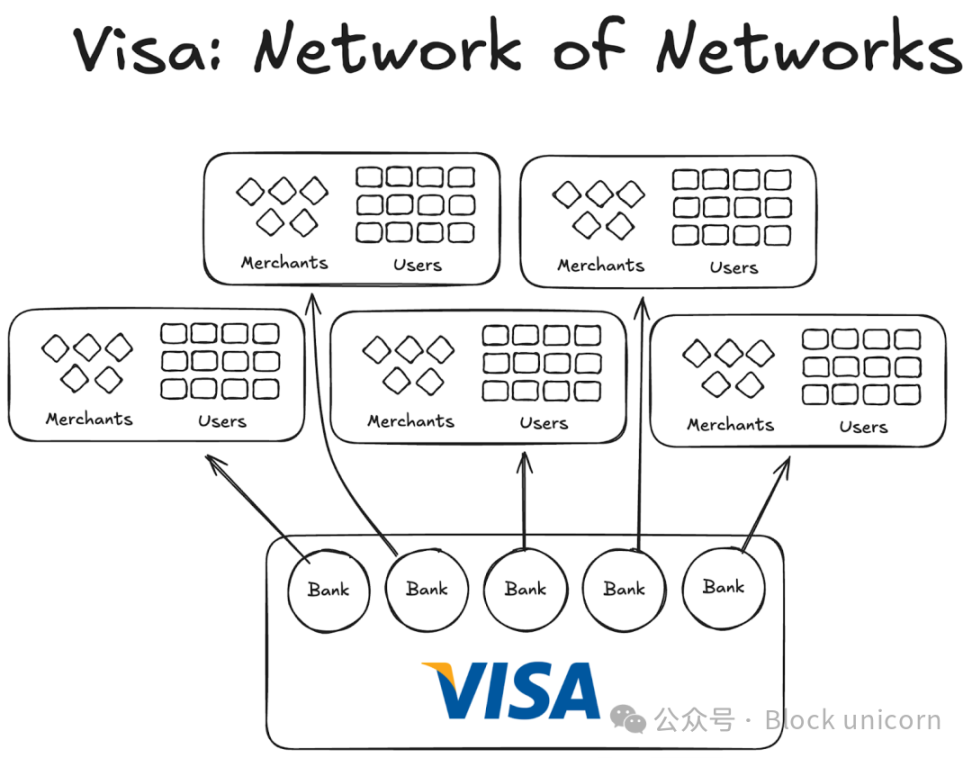

Then Visa emerged. Although the technology it introduced undoubtedly played a significant role in the revolution of bank card payments, its more important success lay in its global universality and its ability to successfully bring banks worldwide into its network. Today, virtually all banks around the globe have become part of the Visa network.

Although this may seem perfectly normal today, imagine trying to convince the first thousand banks, both inside and outside the United States, that it was wise to join a cooperative agreement rather than building their own networks. Only then would you begin to realize the magnitude of this undertaking.

By 1980, Visa had become the dominant payment network, processing about 60% of credit card transactions in the United States. Today, Visa's operations span more than 200 countries.

The key lies not in more advanced technology or greater funding, but in the structure: a model that can coordinate incentive mechanisms, decentralize ownership, and create compound network effects.

Today, stablecoins also face the same problem of fragmentation. The solution might be similar to what Visa did fifty years ago.

Previous experiments with Visa

Other companies that previously appeared, like Visa, were unable to develop successfully.

American Express (AMEX) once attempted to expand its credit card business as an independent bank, but its growth was limited to continuously adding new merchants to its banking network. On the other hand, BankAmericard was different. Bank of America owned its credit card network, and other banks only utilized its network effects and brand value.

American Express had to approach each merchant and user individually to open their bank accounts, whereas Visa achieved scale through its acquiring banks. Every bank that joined Visa's network automatically gained thousands of new customers and hundreds of new merchants.

On the other hand, BankAmericard had infrastructure issues. They didn't know how to efficiently settle credit card transactions from one consumer's bank account to another merchant's bank account. There was no efficient settlement system between them.

The more banks that join, the more severe this problem becomes. Therefore, Visa was created.

The Four Pillars of the Visa Network Effect

From Visa's story, we learned 2-3 key factors that led to the continuous accumulation of its network effects:

Visa benefits from its identity as an independent third party. To ensure that no bank feels threatened by competition, Visa was designed as a collaborative independent organization. Visa does not compete for a share of the distribution pie; instead, it is the banks that compete for their share.

This motivates the participating banks to strive for a larger share of the profits. Each bank is entitled to a portion of the total profit, with the size of the share being proportional to the total volume of transactions it processes.

Banks have a say in the online features. Visa's rules and changes must be voted on by all relevant banks, and they require approval from 80% of the votes to pass.

Visa has exclusive agreements with each bank (at least initially); any bank joining the cooperative can only use Visa cards and the Visa network, and cannot join other networks. Therefore, to interact with Visa banks, you also need to be part of their network.

When Visa's founder Dee Hock was lobbying banks across the United States to join the Visa network, he had to explain to each bank that joining the Visa network was more beneficial than building their own credit card network.

He must explain that joining Visa means more users and more merchants will be connected to the same network, which will facilitate more digital transactions globally and generate greater benefits for all participants. He must also clarify that if they build their own credit card network, their user base will be very limited.

Implications for Stablecoins

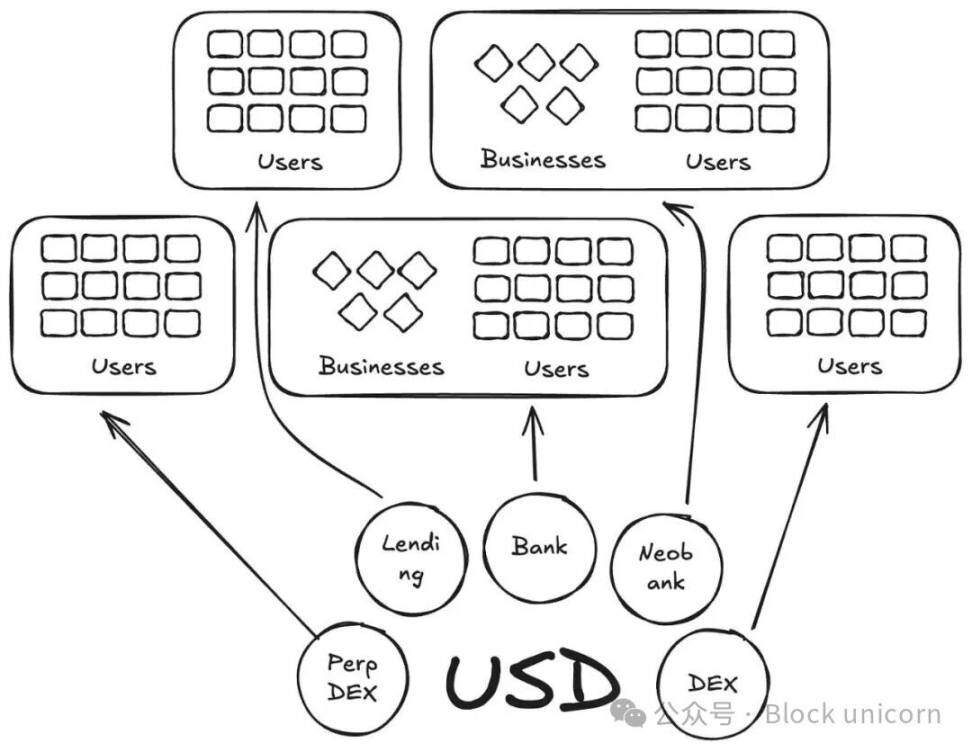

In a way, Anchorage Digital and other companies now offering stablecoin-as-a-service are reenacting the BankAmericard story in the stablecoin space. They provide the underlying infrastructure for new issuers to build stablecoins, while liquidity continues to fragment across new tokens.

Currently, there are already over 300 stablecoins listed on the Defillama platform. Moreover, each newly created stablecoin is limited to its own ecosystem. As a result, no single stablecoin can generate the network effects required for it to achieve mainstream adoption.

If the same underlying assets support these new currencies, why do we need more currencies with new codes?

In our Visa story, these are akin to BankAmericards. Ethena, Anchorage Digital, M0, or Bridge—each allows a protocol to issue its own stablecoin, but this only exacerbates the fragmentation of the industry.

Ethena is another similar protocol that allows yield distribution and white-label customization of its stablecoin. Just like MegaETH issues USDm — they issued USDm through tools supporting USDtb.

However, this model failed. It only fragmented the ecosystem.

In the case of credit cards, brand differences among banks are not significant because they do not create any friction in payments from users to merchants. The underlying issuing and payment layers are always Visa.

However, this is not the case for stablecoins. Different token codes mean an infinite number of liquidity pools.

Merchants (or in this case, applications or protocols) will not add all stablecoins issued by M0 or Bridge to their list of accepted stablecoins. Instead, they will decide based on the liquidity of these stablecoins in the open market. The stablecoins with the highest holder numbers and strongest liquidity should naturally be accepted, while the others will not be.

The Road Ahead: The Visa Model for Stablecoins

We need independent third-party organizations to manage stablecoins across different asset categories. Issuers and applications supporting these assets should be able to join cooperatives and earn returns from reserves. At the same time, they should also have governance rights, enabling them to vote on the direction of the stablecoins they choose.

From the perspective of network effects, this will be an excellent model. As more and more issuers and protocols join the same token, it will facilitate widespread adoption of a token that retains earnings internally rather than allowing them to flow into others' pockets.